Promoting structural change

Pursuit of manufacturing export-led growth has become increasingly challenging, while the rise of digital technologies has transformed the service sector, facilitating cross-border trade. Meanwhile, manufacturing has also become more reliant on service inputs. However, the emerging service export-led growth model is dependent on strong human capital, high-quality infrastructure and well-developed institutional capabilities. Many post-communist economies in the EBRD regions have successfully become top exporters of computer and information services, but other economies should upgrade their infrastructure, skills and institutions in order to excel in the increasingly service-based global economy. Service trade liberalisation and targeted industrial policies can facilitate this shift towards high-value-added service exports, provided that certain economic fundamentals are in place.

Introduction

This chapter looks at structural change and ways of promoting it in the EBRD regions in the context of shifting global trade patterns and the need to diversify sources of growth. Thus far, the history of structural transformation has comprised two distinct phases: a shift from agriculture to manufacturing (industrialisation) and a shift from manufacturing to highly productive services (deindustrialisation or post-industrialisation). While the 20th century was the age of industrialisation, the 21st century is the age of services.

Structural change and labour productivity growth

Economic growth and structural change are closely related. At lower levels of development, gaps between the productivity levels in the various sectors of the economy tend to be large. In other words, capital and labour can become stuck in low-productivity sectors, slowing down economic development. The challenge of development is therefore twofold. There is a structural transformation challenge, which involves ensuring that resources can flow freely and rapidly towards sectors with relatively higher levels of productivity. And there is a challenge in terms of fundamentals, which involves ensuring that the economy accumulates the physical and human capital and institutional capabilities that are necessary to generate sustained economy-wide growth across industry and services, and in both tradeable and non-tradeable sectors of the economy.3

The traditional role of manufacturing in structural transformation

Before 1990, the growth models of many developing economies prioritised industrialisation, supported by investment in capital equipment, technology, education and infrastructure.4 This resulted in manufacturing export-led growth. This trend continued after 1990, but with an important difference: advances in ICT enabled the spatial separation of the various stages of production for a given good. As a result, firms in advanced economies increasingly shifted production to low-cost developing economies, transferring their high-tech know-how at the same time.

The anatomy of structural change in the EBRD regions

In many economies in the EBRD regions, manufacturing’s share of total value added declined sharply in the early 1990s (see Chart 2.1), as did its share of total employment. This reflected overindustrialisation under central planning – especially in heavy industry, where production was highly inefficient and proved unsustainable when exposed to international competition.6

Source: UN Statistics Division, harmonised national accounts and authors’ calculations.

Note: “EBRD economies in the EU (excluding Greece)” comprises Bulgaria, Croatia, Czechia, Estonia, Hungary, Latvia, Lithuania, Poland, Romania, the Slovak Republic and Slovenia. “EEC” refers to eastern Europe and the Caucasus and comprises Armenia, Azerbaijan, Georgia, Moldova and Ukraine. “Central Asia” comprises Kazakhstan, the Kyrgyz Republic, Mongolia, Tajikistan, Turkmenistan and Uzbekistan. “SEMED” denotes the southern and eastern Mediterranean and comprises Egypt, Jordan, Lebanon, Morocco, Tunisia and the West Bank and Gaza. “Western Balkans” comprises Albania, Bosnia and Herzegovina, Kosovo, Montenegro, North Macedonia and Serbia. “Advanced Europe” comprises Austria, Belgium, Cyprus, Denmark, Finland, France, Germany, Iceland, Ireland, Italy, Luxembourg, Malta, the Netherlands, Norway, Portugal, Spain, Sweden, Switzerland and the United Kingdom.

Source: EU KLEMS, Groningen Growth and Development Centre’s Economic Transformation Database (ETD) and Economic Transformation Database of Transition Economies (ETD-TE), and authors’ calculations.

Note: See Box 2.1 for details of the methodology. Each economy is split into 10 sectors: agriculture, mining, manufacturing, utilities, construction, business services (including ICT, professional services, finance, insurance, and real estate), trade services, transport services, government services, and other services (including arts, entertainment, activities of households as employers, and extraterritorial organisations). There are no data available for Lebanon, Mongolia, Turkmenistan, the West Bank and Gaza or the Western Balkans. Data for EU economies relate to the period 1995-2018. “EBRD economies in the EU” comprises Bulgaria, Croatia, Czechia, Estonia, Greece, Hungary, Latvia, Lithuania, Poland, Romania, the Slovak Republic and Slovenia. “EEC and Central Asia” comprises Armenia, Azerbaijan, Georgia, Kazakhstan, the Kyrgyz Republic, Moldova, Tajikistan, Ukraine and Uzbekistan. “SEMED” comprises Egypt, Morocco and Tunisia. “Advanced Europe” comprises Austria, Belgium, Cyprus, Denmark, Finland, France, Germany, Ireland, Italy, Luxembourg, the Netherlands, Portugal, Spain, Sweden and the United Kingdom.

Global innovator services play a key role

In most EBRD regions, as well as China and India, the manufacturing sector’s contribution to economy-wide labour productivity growth has been relatively small in the period since the 1990s (see Chart 2.2). In addition to structural shifts across broad sectors, this reflects improvements in the labour productivity of the service sector, which have, in particular, been made possible by the arrival of digital technologies. These have made services more storable, codifiable and transferable, reducing the need for the producer and the consumer to be in close proximity at the time of delivery, as well as improving their linkages to other sectors. Examples of such services include online banking and call centres. This is akin to the role that ICT played in the spatial separation of production stages in the manufacturing sector in the 1990s, which gave a boost to developing economies with large endowments of cheap low-skilled labour.

Source: EU KLEMS, ETD, ETD-TE and authors’ calculations.

Note: This chart uses the service-sector classification in Nayyar et al. (2021), excluding real estate and construction. See the notes on Chart 2.2 for definitions of the various regions.

Source: EU KLEMS, ETD, ETD-TE and authors’ calculations.

Note: Services are defined as sectors F to U in the International Standard Industrial Classification (ISIC) Rev. 4. The chart total divides services into global innovator services and all other services. The bars show contribution to overall average labour productivity growth for those two groups of services, broken down into the contributions of intra-sector growth (fundamentals) and structural change. Each group of services is treated as one sector. Data for EU economies relate to the period 1995-2018. See the notes on Chart 2.2 for definitions of the various regions.

Goods exports still dominate, but service exports have been growing faster

Structural change can also be seen through the lens of exports of goods and services. Post-communist economies in the EBRD regions experienced a boom in goods exports in the 1990s when they opened up their own markets and obtained better access to foreign markets. In the economies that subsequently joined the EU, for example, average trade-weighted import tariffs dropped from 6.3 per cent in 1995 to 2.4 per cent in 2000. In 2022, goods exports still accounted for more than half of total exports in all EBRD regions: more than 70 per cent in EBRD economies in the EU, the SEMED region, and the EEC region and Central Asia, and over 60 per cent in the Western Balkans and Türkiye – similar to the average of 65.6 per cent seen in the rest of the world (see Chart 2.5). In advanced European economies, on the other hand, goods’ share of total exports has declined to around half, while exports of “other commercial services” (defined as commercial services other than goods-related services, transport and travel services) accounted for more than a third of all exports in 2022. In comparison, such service exports accounted for 13 per cent of total exports in the Western Balkans in 2022 (the largest share in the EBRD regions) and only 5 per cent in the SEMED region.

Source: CEPII BACI dataset, Trade in Services data by Mode of Supply (TiSMoS) dataset produced by the World Trade Organization (WTO) and authors’ calculations.

Note: Shares are calculated as unweighted averages of country-level values. “Other commercial services” comprise construction, insurance and pension services, financial services, charges for the use of intellectual property not elsewhere classified, ICT services, other business services, and personal, cultural and recreational services. The category not shown consists of manufacturing services relating to physical inputs owned by others, maintenance and repair services not included elsewhere, transport services, distribution services, and tourism and travel services. See the notes on Chart 2.1 for definitions of the various regions. There are no data available for the West Bank and Gaza.

Several economies in the EBRD regions are excelling in exports of ICT services

Worldwide, the sectors with the highest average compound annual growth rates for exports of digitally enabled services are computer services (15.9 per cent), advertising, market research and public opinion polling services (14.1 per cent), and legal, accounting, management, consulting and public relations services (12.6 per cent). In the EBRD regions, average compound annual growth rates for these sectors are around the same level or higher. Several EBRD economies have also seen strong growth in the information service sector.

Source: WTO TiSMoS dataset, World Bank World Development Indicators (WDIs) and authors’ calculations.

Note: Ireland and Cyprus are excluded because their exports are dominated by foreign-owned multinational enterprises that use those countries as centralised locations for overseeing elements of their value chains owing to the favourable tax regimes. There are no data available for Montenegro in 2005.

Human capital and shifting demand for skills

Compared with countries at a similar level of development, most EBRD regions have had relatively well-educated populations since at least the early 1990s (see Chart 2.7). This, too, is a legacy of communist systems, which emphasised education and skills as public goods serving the needs of society rather than individual interests. Education was free and mandatory, with emphasis placed on the specialist vocational and technical skills and knowledge that were required for industrial development.22 This means that post-communist economies are well placed to provide high-productivity tradeable services such as ICT services, which require a highly skilled workforce.23 Box 2.2, for example, illustrates the role that human capital has played in the success of Romania’s computer and information service sector.

Source: Barro-Lee Educational Attainment Dataset (see Barro and Lee, 2013), Maddison Project, World Bank WDIs and authors’ calculations.

Note: “EBRD economies in the EU (excluding Greece)” comprises Bulgaria, Croatia, Czechia, Estonia, Hungary, Latvia, Lithuania, Poland, Romania, the Slovak Republic and Slovenia. “Western Balkans” includes data for Serbia and Albania only. “EEC and Central Asia” comprises Armenia, Kazakhstan, the Kyrgyz Republic, Moldova, Mongolia, Tajikistan and Ukraine. “SEMED” comprises Egypt, Jordan, Morocco and Tunisia. “Advanced Europe” comprises Austria, Belgium, Cyprus, Denmark, Finland, France, Germany, Iceland, Ireland, Italy, Luxembourg, Malta, the Netherlands, Norway, Portugal, Spain, Sweden, Switzerland and the United Kingdom. “Other emerging market economies” comprises all other economies with available data that are classified as middle income in the World Bank’s 1995 income group classification.

Source: EU KLEMS, ETD, ETD-TE, UNIDO CIP index and authors’ calculations.

Note: “Medium- and high-technology-intensive manufacturing sectors” are defined as all manufacturing sectors except food products and beverages, tobacco, textiles, textile products, leather and footwear, wood and wood products, paper and paper products, printing and publishing, furniture, manufacturing not elsewhere classified and recycling.29 See the notes on Chart 2.2 for definitions of the various regions. “Others” comprises all other economies with the required data.

Source: EU LFS, O*NET (releases 5.0, 10.0, 16.0, 21.0 and 24.0) and authors’ calculations based on Acemoğlu and Autor (2011).

Note: O*NET-SOC classifications are mapped to one-digit International Standard Classification of Occupations (ISCO) codes in the EU LFS. Each composite index is calculated as the sum of constituent task items based on Acemoğlu and Autor (2011), standardised within each country and re-scaled so that the figure for 1998 is 0. See Box 2.1 for more details. “Advanced Europe” comprises Austria, Belgium, Denmark, Finland, France, Germany, Iceland, Ireland, Italy, Luxembourg, the Netherlands, Norway, Portugal, Spain, Sweden, Switzerland and the United Kingdom. “EBRD economies in the EU” comprises Czechia, Estonia, Greece, Hungary, Latvia, Lithuania, Romania, the Slovak Republic and Slovenia. Bulgaria, Croatia, Cyprus, Malta and Poland are not included owing to a lack of available data for 1998.

Source: EU LFS, O*NET (releases 5.0, 10.0, 16.0, 21.0 and 24.0) and authors’ calculations.

Note: For details, see the note accompanying Chart 2.9.

Links between manufacturing and services

Is manufacturing export-led growth still possible?

The increase in the geographical concentration of manufacturing production and the slowdown in the growth of manufacturing exports since 2008 raises the question of whether manufacturing export-led growth is still possible. Growth can be thought of as export-led if the domestic value added that is embodied in exports grows faster than GDP. Export-led growth can, in turn, be led by (i) manufacturing only, (ii) services only (with “services” referring to global innovator services) or (iii) both manufacturing and services.30

Source: OECD TiVA database and authors’ calculations.

Note: Growth led by manufacturing exports is defined as a situation where the domestic value-added content of manufacturing gross exports grows faster than GDP. Growth led by service exports is defined as a scenario in which the domestic value added content of gross exports of global innovator services grows faster than GDP. “Other EBRD economies” comprises Egypt, Jordan, Kazakhstan, Morocco, Tunisia, Türkiye and Ukraine. “Other emerging market economies” comprises Argentina, Belarus, Brazil, Chile, Colombia, Costa Rica, Indonesia, Malaysia, Mexico, Peru, the Philippines, Russia, Saudi Arabia, South Africa and Thailand.31 “Advanced Europe” and “EBRD economies in the EU” are as defined in Chart 2.1, except for the fact that the latter includes Greece here.

Source: Barro-Lee Educational Attainment Dataset, World Bank WGIs, World Bank-WTO Services Trade Restrictions Index (STRI) database and authors’ calculations.

Note: For each economy, this chart plots average years of schooling in 2010 against a score calculated as the first principal component of (i) a set of WGI indicators measuring voice and accountability, political stability and the absence of violence, government effectiveness, regulatory quality, the rule of law and control of corruption, and (ii) STRI scores for trade in computer, communications, financial and professional services derived from the World Bank-WTO STRI database. See the notes on Chart 2.2 for definitions of the various regions. “Others” comprises all other economies with the required data.

Increase in the service content of manufacturing

Not only is manufacturing export-led growth being replaced by service export-led growth, manufacturing is also – as a result of the fragmentation of production in global value chains (GVCs) – becoming increasingly reliant on services, whether as intermediate inputs, as activities within firms or as services sold together with goods to add more value.32 This phenomenon, referred to as the “servicification” of manufacturing, can be traced back to the ICT revolution of the 1990s.33

Source: OECD TiVA database (2023 edition) and authors’ calculations.

Note: Shares are calculated as unweighted averages of country-level values. The shares of skill-intensive social services (not shown) are small. See the notes on Chart 2.11 for definitions of the various regions.

Source: EU KLEMS, EU LFS, World Bank WDIs and authors’ calculations.

Note: Data on service-related occupations’ share of total employment in the manufacturing sector and value added per worker in manufacturing are unweighted averages of the figures for the various countries. “Advanced Europe” comprises Austria, Belgium, Cyprus, Denmark, Finland, France, Germany, Italy, Luxembourg, the Netherlands, Portugal, Spain, Sweden and the United Kingdom. “EBRD economies in the EU” comprises Bulgaria, Czechia, Estonia, Greece, Hungary, Latvia, Lithuania, Poland, Romania, the Slovak Republic and Slovenia. Ireland has been omitted, since it is an outlier. Croatia, Iceland, Malta, Norway and Switzerland are not included owing to a lack of available data.

Hungary case study

The Hungarian economy is strongly integrated into GVCs, particularly in sectors such as the automotive industry, electronics, pharmaceuticals and food. In 2020, participation in GVCs accounted for 62 per cent of Hungary’s gross exports according to estimates in the OECD’s TiVA database – second only to the Slovak Republic in the EBRD regions and the fifth highest out of 76 economies around the world.

Firm-level data from Hungary can thus provide useful insights into the “servicification” of the manufacturing sector, as well as trade in services more broadly.35 Goods and services are traded across borders by manufacturing firms and tradeable service firms alike,36 but the percentage of firms that are engaged in international trade tends to be lower in the service sector. Moreover, firms are more likely to trade goods than services (see Chart 2.15).

Almost all of Hungary’s manufacturing firms export goods before they start exporting services. However, over time, some are able to add complementary services (referred to as “servitisation”37), which may mean moving up the value-added ladder. Examples include bundling “other plastic articles” with “engineering services”, or “iron or steel articles” with “maintenance and repair services”. In 2019, almost two-thirds of goods exports by value were accompanied by services exported by the same firm to the same destination – a 20 percentage point increase relative to 2008.

Foreign investment has been a key driver of this trend. Foreign-owned manufacturing firms (defined as those where foreign ownership totals at least 50 per cent) are much more likely than domestic firms to trade across borders, especially as two-way traders that export and import both goods and services. Such two-way traders in goods and services accounted for 17.5 per cent of all foreign-owned manufacturing firms in 2019, up from 9.2 per cent in 2008, pointing to an increase in the “servicification” of Hungarian manufacturing, driven by participation in GVCs. In contrast, only 0.7 per cent of domestic firms were two-way traders in both goods and services in 2019. Not surprisingly, most of Hungary’s top five exporters of services by export value are foreign-owned.

Increasingly, services are digitally enabled, so being close to customers is less important for suppliers of services than for manufacturers of goods. As a result, value-weighted average export distances are longer for service exports than for goods exports – 2.4 times longer in 2019 for Hungarian firms that export both goods and services. Of the top 10 destinations for service exports, 7 are in the 10 foreign investor countries with the largest subsidiaries in Hungary (Germany, the United States, Austria, France, the United Kingdom, the Netherlands and Switzerland).38

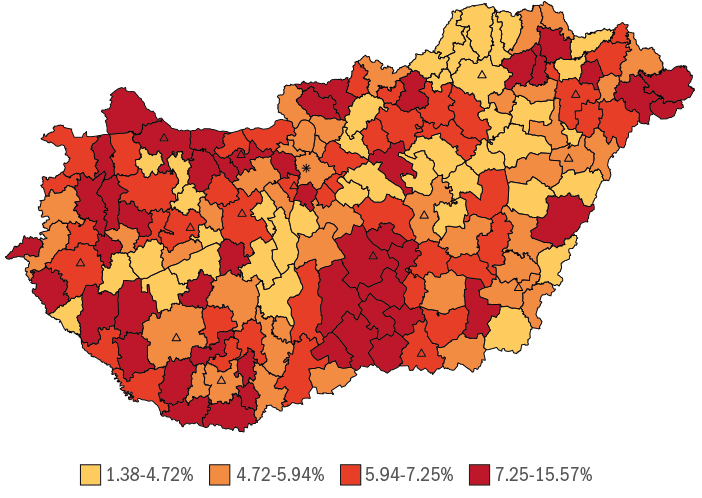

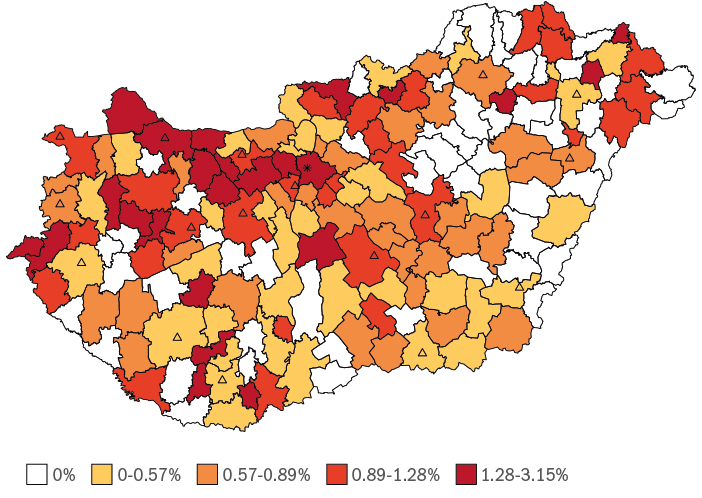

Firms that export services tend to be larger and more productive than those that export only goods, and they tend to pay higher wages. They are also more likely to be foreign-owned and clustered in or around large cities with strong skill bases (see Chart 2.16, which shows the percentage of firms that export goods and services at the level of 174 districts). Several multinational companies have set up R&D centres in Hungary (with Audi and Thyssenkrupp doing so in Győr and Budapest, respectively).39 There are also close to 100 shared service centres operating in Hungary, serving companies such as Deutsche Telekom, IBM, Tata Consultancy Services, Citi and BP, as well as business process outsourcing (BPO) companies such as Avaya and Ubiquity (most of which are based in Budapest).40 The majority of Hungary’s large software companies are located in Budapest.[/expander]

Source: Bisztray et al. (2024), Hungarian Central Statistical Office and authors’ calculations.

Note: “Foreign-owned” firms are defined as those where foreign ownership totals at least 50 per cent. “One way trade in services” comprises firms that are one-way traders in services and either (i) trade goods one-way or (ii) do not trade goods at all.

Goods exporters as a percentage of all firms, 2019

Service exporters as a percentage of all firms, 2019

Source: Bisztray et al. (2024), Hungarian Central Statistical Office and authors’ calculations.

Note: The star denotes Budapest, while the triangles denote other cities with populations of 50,000 or more.

How can we foster a shift to productive services?

How does structural change happen?

The shift from agriculture to manufacturing did not require significant investment in the skills of workers.41 Neither did it require wide-ranging improvements to governance or regulatory frameworks, as these changes could often be confined to special economic zones or customised policy regimes, with only modest institutional improvements – if any – at the level of the economy as a whole. The required machinery, equipment and technology could be imported or obtained by attracting foreign direct investors, and access to global markets could, to a large extent, be achieved through the liberalisation of trade in goods.

Liberalisation of trade in services

The early 1990s saw the EBRD regions open their economies to the world, removing tariff and non-tariff barriers to trade in goods – a crucial step in their transition to market economies. The liberalisation of goods trade allowed those countries to overcome legacies of central planning such as distorted pricing systems, poor productivity and outdated technology. However, the pace and extent of trade reforms varied across economies owing to differences in countries’ initial circumstances and their approach to reforms. In particular, central European countries and the Baltic states benefited from their geographical proximity to advanced European markets and more successful and rapid macroeconomic stabilisation.44

Source: OECD Services Trade Restrictiveness Index (STRI) and authors’ calculations.

Note: The bars show STRI scores for trade in computer services in 2023. For EEA countries, dots indicate STRI scores for intra-EEA trade in computer services in the same year. Scores are on a scale of 0 to 1, where 0 denotes a complete absence of restrictions.

Restrictions on trade in services have a detrimental impact

What gains could be made in terms of trade in services if sector-specific restrictions or restrictions on digital trade were relaxed? The gravity model of international trade postulates that trade flows between two countries are dependent on the countries’ economic size, the geographical distance between them and the extent of any frictions impeding bilateral trade (which are typically alleviated by shared borders, common languages, common legal systems, shared colonial legacies and regional trade agreements).

Source: OECD-WTO Balanced Trade in Services (BaTIS) database (BPM6 edition), OECD STRI database, CEPII Gravity database and authors’ calculations.

Note: This chart shows the estimated change in service exports that is derived by regressing bilateral service exports on the characteristics listed on the horizontal axis using a Poisson pseudo-maximum-likelihood (PPML) estimator (see Santos Silva and Tenreyro, 2006). The regression includes sector and year fixed effects and covers transport services, insurance and pension services, financial services, ICT services, other business services, and personal, cultural and recreational services. As these sectors are broader than the sectors for which STRI scores are available, weights based on data in the WTO’s TiSMoS dataset are used to calculate weighted average STRI scores (see Box 2.1). The 95 per cent confidence intervals shown are based on standard errors clustered at the level of trading pairs.

Can investment promotion facilitate structural change?

Most countries have investment promotion agencies – government bodies that are tasked with attracting businesses and investment to the country. Most IPAs target specific sectors when attracting FDI, and investment promotion can therefore be viewed as an industrial policy.

Source: FT fDi Markets database, O’Reilly and Murphy (2022) and authors’ calculations.

Note: This chart shows the estimated coefficients derived from a difference-in-differences regression comparing targeted sectors with not-yet-targeted and never-targeted sectors in terms of the number of FDI projects at country-sector-year level, looking at service-oriented and manufacturing-oriented projects separately. For service-oriented projects, separate estimates are shown for countries with below-median and above-median levels of state capacity. Spikes indicate 95 per cent confidence intervals based on standard errors clustered at the country-sector level.

Conclusion and policy implications

The sectors that are thriving in the 21st century are significantly different from those that prospered most in the 20th century. With the pursuit of manufacturing export-led growth becoming increasingly difficult for most countries, the prospect of service export-led growth beckons. The advent of digital technologies promises to revolutionise the delivery of services around the world, much as ICT transformed manufacturing in the 1990s.

Of the various services, digitally enabled tradeable services – especially global innovator services – have the most potential for growth. These are the services that have played the largest role in the recent improvements in labour productivity within the service sector, and they have strong connections to other economic sectors. At the same time, services are also playing an increasingly important role within the manufacturing sector, both as inputs for manufactured goods (as in the case of design services, R&D, supply chain logistics and marketing, for example) and as products bundled together with goods (such as installation, support, maintenance and repair services). By contrast with the assembly of manufactured goods, such higher-value-added services are dependent on a relatively high level of human capital.

In order to strengthen countries’ competitiveness in today’s service-oriented economy, policymakers should prioritise fundamentals such as digital infrastructure, governance and education, with emphasis on the skills that are required by global innovator services. As the example of Romania shows (see Box 2.2), targeted industrial policies can help to further accelerate the transition to more productive service sectors, provided that the necessary fundamentals are in place.

Lowering restrictions on trade in services can be an effective way of boosting service exports, particularly for digitally enabled services. At the same time, lowering restrictions does not necessarily mean having a regime where anything goes. For example, GDPR-equivalent legislation has been found to facilitate trade in services by establishing fair and transparent rules governing the handling of data.

Firms and workers may require targeted assistance in order to use the new digital technologies effectively, which could, for example, involve the provision of management training or technology training, or the award of loans or grants, particularly for smaller firms.54 In order to help less educated workers to acquire the skills needed to transition to more productive employment in the service sector, and to improve firms’ productivity, training programmes should be developed in close collaboration with employers to better understand their needs.

Box 2.1. Databases and definitions

Breakdown into structural change and fundamentals

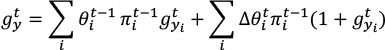

This chapter uses the following decomposition for economy-wide labour productivity growth ![]() .55

.55

The first term represents the sum of the intra-sectoral productivity growth components for the various sectors indexed ![]() (fundamentals). The second term captures the contribution made by the reallocation of labour between sectors (structural change).

(fundamentals). The second term captures the contribution made by the reallocation of labour between sectors (structural change). ![]() denotes sector-specific labour productivity,

denotes sector-specific labour productivity, ![]() is annual growth in labour productivity (

is annual growth in labour productivity (  and

and  ),

), ![]() is sector

is sector ![]() ’s share of total employment,

’s share of total employment, ![]() is the relative labour productivity in sector

is the relative labour productivity in sector ![]() , defined as

, defined as ![]() , and denotes

, and denotes ![]() time. Labour productivity is measured as value added per employee. Data are taken from the Groningen Growth and Development Centre’s Economic Transformation Database and Economic Transformation Database of Transition Economies, and EU KLEMS.56

time. Labour productivity is measured as value added per employee. Data are taken from the Groningen Growth and Development Centre’s Economic Transformation Database and Economic Transformation Database of Transition Economies, and EU KLEMS.56

Defining global innovator services

Global innovator services are defined as those in ISIC Rev. 4 sectors J (information and communication), K (financial and insurance activities) and M (professional, scientific and technical activities). The Groningen Growth and Development Centre aggregates data on information and communication (sector J), professional, scientific and technical activities (sector M) and administrative and support services (sector N) in “business services”, so data on global innovator services that use the Groningen Growth and Development Centre datasets include sector N in addition to sectors J, K and M.

Databases capturing trade in services

Measuring trade in services is difficult. Unlike goods, many services do not pass through customs, unless they are embodied in goods (such as software on a DVD) or involve the movement of goods (as in the case of transport services). In some cases, it is the provider – rather than the service itself – that crosses the border (for example, in the case of a Polish management consultant working on a project in Germany). In other cases, it is the consumers of services who are the ones crossing borders (as in the case of German tourists visiting Croatia).

Mapping the task content of jobs from O*NET to the EU LFS

The importance scores for task items in the O*NET-SOC occupational taxonomy were linked to the EU LFS microdata by mapping US SOC occupational codes to one-digit ISCO occupations. To allow for task content changes within occupations over time, the analysis used five different releases of the O*NET database (5.0, 10.0, 16.0, 21.0 and 24.0). Task intensities for each occupation and year were calculated using a linear interpolation between the importance scores for the two nearest O*NET releases, with weights inversely proportionate to the periods of time between the year in question and the respective release dates. Occupations in the armed forces were excluded from the analysis.

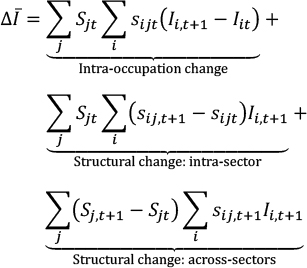

Decomposing non-routine cognitive task intensity

Using a three-way decomposition, the economy-wide change in non-routine cognitive task intensity that is observed over time can be broken down into an intra-occupation component and two structural change components that account for intra-sectoral and cross-sector changes in task intensities as follows:

where ![]() the non-routine cognitive task intensity of occupation

the non-routine cognitive task intensity of occupation ![]() in year

in year ![]() ,

, ![]() is occupation

is occupation ![]() ’s share of employment within sector

’s share of employment within sector ![]() in year

in year ![]() , and

, and ![]() is sector

is sector ![]() ’s share of employment in the economy in year

’s share of employment in the economy in year ![]() . To ensure consistency over the period studied, this analysis is based on 12 groups of NACE Rev. 1.1 sectors: A and B (agriculture, hunting and forestry; and fishing); C (mining and quarrying); D (manufacturing); E (electricity, gas and water supply); F (construction); G (wholesale and retail trade; and repair of motor vehicles, motorcycles and personal and household goods); H (hotels and restaurants); I (transport, storage and communication); J (financial intermediation); K (real estate, renting and business activities); L, M and N (government services); and O, P and Q (other services).

. To ensure consistency over the period studied, this analysis is based on 12 groups of NACE Rev. 1.1 sectors: A and B (agriculture, hunting and forestry; and fishing); C (mining and quarrying); D (manufacturing); E (electricity, gas and water supply); F (construction); G (wholesale and retail trade; and repair of motor vehicles, motorcycles and personal and household goods); H (hotels and restaurants); I (transport, storage and communication); J (financial intermediation); K (real estate, renting and business activities); L, M and N (government services); and O, P and Q (other services).

Calculating employment in embodied services in manufacturing

Manufacturing can broadly be divided into core activities (operations and assembly) and supporting functions that could be outsourced as services (R&D, design activities, logistics, marketing, IT, management and so on).61 Using EU LFS data, and mapping ISCO-88 to ISCO-08 at the one-digit level, employees within the manufacturing sector can be crudely assigned to either core manufacturing activities or support functions, with the latter effectively representing embodied services within the manufacturing sector.62

Hungarian firm-level data

The analysis of Hungarian firms trading in goods and services is based on a combination of four datasets using anonymous firm identifiers: a trade in services database (with data available at the firm-BPM service-source/destination country-year level); a trade in goods database (with data available at the firm-HS6 product-source/destination country-year level); balance sheet and profit and loss statements; and firm registry data. The trade in services database covers a sample of firms that export or import a considerable amount of services (based on their VAT statements and corporate tax returns).

The OECD’s STRI and DSTRI databases

The nature of restrictions on trade in services, which are spread across multiple country-specific laws and regulations, makes them difficult to record in a consistent and comparable manner across countries.63 In 2014 the OECD introduced its Services Trade Restrictiveness Index, which assesses measures affecting trade in 18 service sectors in 50 countries, including 11 economies in the EBRD regions. The sectors covered are: construction; wholesale and retail trade; freight rail transport; freight transport by road; water transport; air transport; warehousing and storage; cargo handling; postal and courier services; motion pictures, video and television; sound recording and music publishing; programming and broadcasting activities; telecommunications; computer services; financial service activities, except insurance and pensions; insurance, reinsurance and pension funds; accounting, bookkeeping and auditing; and legal services.64 For members of the European Economic Area, there is a separate services trade restrictiveness index.65 STRI scores assess restrictions on foreign entry and the movement of people, barriers to competition, other discriminatory measures and regulatory transparency. On average, trade in sound recording and music publishing is the least restricted area, while trade in air transport services is the most heavily restricted.

Sectors targeted by investment promotion agencies and the FT fDi Markets database

The sectors included in the EBRD’s IPA survey were based on ISIC Rev. 4, covering a wide range of primary, manufacturing and service industries. Meanwhile, the FT fDi Markets database uses its own custom sector classification system. To bridge this gap between the two classifications, each FDI project in the FT fDi Markets database was matched to the most appropriate IPA survey sector using the Claude 3.5 Sonnet API on the basis of the project’s subsector information provided in the FT fDi Markets database.

Romanian firm-level data

These data come from Bureau van Dijk’s Orbis database and cover the period 2010-16. They are processed using the methodology developed in Kalemli-Ozcan et al. (2024). In addition, firms with missing information on employment, operating revenue or total assets for any year between 2012 and 2014 are excluded, as are firms with zero employees in any year between 2010 and 2016. The employees of firms in NACE Rev 2. sectors 58.21, 58.29, 62.01, 62.02 and 62.09 are considered to be eligible for the income tax cut; firms in ineligible ICT service sectors and the scientific R&D service sector are used as a control group.67

| STRI sector code | STRI sector name | BaTIS sector code | BaTIS sector name | TiSMoS sector code | TiSMoS sector name |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| F | Construction | SE | Construction | SE | Construction |

| G | Wholesale and retail trade | N/A | N/A | SW | Trade margins of wholesalers and retailers |

| H4912 | Freight rail transport | SC | Transport | SC32 | Freight (other) |

| H4923 | Freight transport by road | SC1 | Sea transport | ||

| H50 | Water transport | SC2 | Air transport | ||

| H51 | Air transport | SC13, 23, 33 | Other (sea) + Other (air) + Other (other) | ||

| H521 | Warehousing and storage | SC4 | Postal and courier services | ||

| H5224 | Cargo handling | ||||

| H53 | Postal and courier activities | ||||

| J591 | Motion picture, video and television | SK* | Personal, cultural and recreational services | SK1 | Audio-visual and related services |

| J592 | Sound recording and music publishing | ||||

| J60 | Programming and broadcasting activities | ||||

| J61 | Telecommunications | SI* | Telecommunications, computer and information services | SI1 | Telecommunications services |

| J62_63 | Computer programming, consultancy and information service activities | SI2+SI3 | Computer services + Information services | ||

| K64 | Financial service activities, except insurance and pensions | SG* | Financial services | SG | Financial services |

| K65 | Insurance, reinsurance and pension funds | SF* | Insurance and pension services | SF | Insurance and pension services |

| M691 | Legal activities | SJ* | Other business services | SJ21 | Legal, accounting, management, consulting and public relations |

| M692 | Accounting, bookkeeping and auditing | ||||

| N/A | N/A | SH* | Charges for the use of intellectual property | SH | Charges for the use of intellectual property not included elsewhere |

Source: OECD-WTO BaTIS database, WTO TiSMoS database and OECD STRI database.

Note: * denotes sectors covered by the DSTRI database.

Box 2.2. Exports of computer and information services and human capital: evidence from Romania

Romania’s emergence as a significant hub for computer and information services in eastern Europe has resulted in it being compared to Silicon Valley. This success story exemplifies the benefits of global innovator services as an engine of growth, highlighting a key lesson from this chapter: well-crafted industrial policies that build on pre-existing fundamentals can promote structural change and growth in high-productivity services.

Source: EU KLEMS, WTO TiSMoS database and authors’ calculations.

Note: Data for “other EBRD economies in the EU” are unweighted averages of national data and cover Bulgaria, Croatia, Czechia, Estonia, Hungary, Latvia, Lithuania, Poland, the Slovak Republic and Slovenia. The computer and information service sectors are defined as NACE Rev 2. codes 62 and 63 in EU KLEMS and EBOPS 2010 codes SI2 and SI3 in TiSMoS.

Source: Bureau van Dijk’s Orbis database, 1992 Romanian census, Manelici and Pantea (2021) and authors’ calculations.

Note: This chart shows the estimated coefficients derived from a difference-in-differences regression comparing computer and information service firms that were eligible to benefit from the 2013 tax reform with ineligible firms in the control group. The subsamples cover eligible firms located in NUTS-3 regions with an above-median stock of STEM-enabling human capital in 1992 (prior to the global ICT boom) and eligible firms in regions with a below-median stock of such human capital. The endowment of STEM-enabling human capital is captured by the first principal component of indicators such as (i) the percentage of workers in computer-related professions, (ii) university graduates as a percentage of the workforce, (iii) the ratio of universities to people of university age, and (iv) the percentage of workers in STEM-related professions, with all data relating to 1992. Firm employment is winsorised at the 1st and 99th percentiles.

Box 2.3. Morocco’s automotive sector

The example of Morocco shows how a well-designed industrial policy can help countries increase their participation in global value chains for manufacturing. This can be achieved by expanding production and moving up the value chain, even in highly competitive global markets.72

Source: CEPII BACI dataset (2002 vintage), World Bank WDIs and authors’ calculations.

Note: The synthetic controls have been constructed at the HS2 level and relate to codes 87 (automotive sector) and 88 (aerospace sector).

References

D. Acemoğlu and D.H. Autor (2011)

“Chapter 12 – Skills, tasks and technologies: Implications for employment and earnings”, in D. Card and O. Ashenfelter (eds.), Handbook of Labor Economics, Vol. 4, Part B, Elsevier, pp. 1043-1171.

AfDB, EBRD and EIB (2021)

Private Sector Development in Morocco: Challenges & Opportunities in Times of Covid-19, joint report.

J.M. Arnold, B. Javorcik and A. Mattoo (2011)

“Does services liberalization benefit manufacturing firms? Evidence from the Czech Republic”, Journal of International Economics, Vol. 85, No. 1, pp. 136-146.

M. Atolia, P. Loungani, M. Marquis and C. Papageorgiou (2020)

“Rethinking development policy: What remains of structural transformation?”, World Development, Vol. 128, Article 104834.

D.H. Autor (2015)

“Why Are There Still So Many Jobs? The History and Future of Workplace Automation”, The Journal of Economic Perspectives, Vol. 29, No. 3, pp. 3-30.

L. Baiker, I. Borchert, J. Magdeleine and J.A. Marchetti (2023)

“Services trade policies across Africa: New evidence for 54 economies”, World Bank Policy Research Working Paper No. 10537.

R. Baldwin (2024a)

“Is export-led development even possible anymore?”, LinkedIn, 7 June. Available at: www.linkedin.com/pulse/export-led-development-even-possible-anymore-richard-baldwin-nusge (last accessed on 21 July 2024).

R. Baldwin (2024b)

“Why is manufacturing-export-led growth so difficult?”, LinkedIn, 14 June. Available at: www.linkedin.com/pulse/why-manufacturing-export-led-growth-so-difficult-richard-baldwin-vb6he (last accessed on 21 July 2024).

R.J. Barro and J.-W. Lee (2013)

“A New Data Set of Educational Attainment in the World, 1950-2010”, Journal of Development Economics, Vol. 104, pp. 184-198.

S. Benz and F. Gonzales (2019)

“Intra-EEA STRI database: Methodology and results”, OECD Trade Policy Paper No. 223.

M. Bisztray, B. Javorcik and H. Schweiger (2024)

“Services exporters and importers in Hungary”, KRTK-KTI working paper, forthcoming.

A. Bollard, P.J. Klenow and G. Sharma (2013)

“India’s mysterious manufacturing miracle”, Review of Economic Dynamics, Vol. 16, No. 1, pp. 59-85.

F. Bontadini, C. Corrado, J. Haskel, M. Iommi and C. Jona-Lasinio (2023)

“EUKLEMS & INTANProd: industry productivity accounts with intangibles. Sources of growth and productivity trends: methods and main measurement challenges”, LUISS Lab of European Economics. Available at: https://euklems-intanprod-llee.luiss.it/wp-content/uploads/2023/02/EUKLEMS_INTANProd_D2.3.1.pdf (last accessed on 9 August 2024).

I. Borchert, B. Gootiiz, J. Magdeleine, J.A. Marchetti, A. Mattoo, E. Rubio and E. Shannon (2020)

“Applied services trade policy: A guide to the Services Trade Policy Database and the Services Trade Restrictions Index”, WTO Staff Working Paper No. ERSD-2019-14.

K. Borusyak, X. Jaravel and J. Spiess (2024)

“Revisiting event-study designs: Robust and efficient estimation”, The Review of Economic Studies.

F. Coelli, D. Ouyan, W. Yuan and Y. Zi (2023)

“Educating like China”, mimeo, November. Available at: https://drive.google.com/file/d/1CbzPMFM3x6YixxXt8KI0FTd7-soGq6lv/view?usp=drive_link (last accessed on 7 August 2024).

T. Conefrey, E. Keenan, M. O’Grady and D. Staunton (2023)

“The role of the ICT services sector in the Irish economy”, Quarterly Bulletin Q1 2023, Central Bank of Ireland, March, pp. 86-105.

M. Crozet and E. Milet (2017)

“Should everybody be in services? The effect of servitization on manufacturing firm performance”, Journal of Economics & Management Strategy, Vol. 26, No. 4, pp. 820-841.

Cyprus Economy and Competitiveness Council (2022)

2021 Cyprus Competitiveness Report, Nicosia. Available at: https://economy-finance.ec.europa.eu/system/files/2022-03/2021_cyprus_competitiveness_report.pdf (last accessed on 8 August 2024).

X. Diao, M. McMillan and D. Rodrik (2019)

“The recent growth boom in developing economies: A structural-change perspective”, in M. Nissanke and J.A. Ocampo (eds.), The Palgrave Handbook of Development Economics, Palgrave Macmillan, pp. 281-334.

EBRD (2023)

Transition Report 2023-24 – Transitions Big and Small, London.

J. Ferencz (2019)

“The OECD Digital Services Trade Restrictiveness Index”, OECD Trade Policy Paper No. 221.

I. Frumin and D. Platonova (2024)

“The socialist model of higher education: The dream faces reality”, Dædalus, Vol. 153, No. 2, pp. 178-193.

G. Gaulier and S. Zignago (2010)

“BACI: International Trade Database at the Product-Level. The 1994-2007 Version”, CEPII Working Paper No. 2010-23.

M. Geloso Grosso, F. Gonzales, S. Miroudot, H.K. Nordås, D. Rouzet and A. Ueno (2015)

“Services trade restrictiveness index (STRI): Scoring and weighting methodology”, OECD Trade Policy Paper No. 177.

C. Hamilton and G.J. de Vries (2023)

“The structural transformation of transition economies”, GGDC Research Memorandum No. 196, University of Groningen.

T. Harding and B. Javorcik (2011)

“Roll out the red carpet and they will come: Investment promotion and FDI inflows”, The Economic Journal, Vol. 121, No. 557, pp. 1445-1476.

W. Hardy, R. Keister and P. Lewandowski (2018)

“Educational upgrading, structural change and the task composition of jobs in Europe”, Economics of Transition and Institutional Change, Vol. 26, No. 2, pp. 201-231.

B. Hoekman (2016)

“Intra-Regional Trade: Potential Catalyst for Growth in the Middle East”, MEI Policy Paper No. 2016-1, Middle East Institute.

B. Javorcik, B. Kett, K. Stapleton and L. O’Kane (2024)

“Unravelling deep integration: Local labour market effects of the Brexit vote”, Journal of the European Economic Association, forthcoming.

S. Kalemli-Ozcan, B.E. Sørensen, C. Villegas-Sanchez, V. Volosovych and S. Yeşiltaş (2024)

“How to construct nationally representative firm-level data from the Orbis global database: New facts on SMEs and aggregate implications for industry concentration”, American Economic Journal: Macroeconomics, Vol. 16, No. 2, pp. 353-374.

A.I. Kaya and C. Ciçekçi (2023)

“Structural transformation and sources of growth in Turkey”, WIDER Working Paper No. 2023/71.

H. Kruse, E. Mensah, K. Sen and G.J. de Vries (2022)

“A manufacturing (re)naissance? Industrialization in the developing world”, IMF Economic Review, Vol. 71, pp. 439-473.

A. Liberatore and S. Wettstein (2021)

“The OECD-WTO Balanced Trade in Services database (BaTIS)”. Available at: www.oecd.org/content/dam/oecd/en/data/methods/OECD-WTO-Balanced-Trade-in-Services-database-methodology-BPM6.pdf (last accessed on 4 August 2024).

I. Manelici and S. Pantea (2021)

“Industrial policy at work: Evidence from Romania’s income tax break for workers in IT”, European Economic Review, Vol. 133, Article 103674.

M. McMillan and D. Rodrik (2011)

“Globalization, structural change and productivity growth”, in M. Bacchetta and M. Jansen (eds.), Making Globalization Socially Sustainable, International Labour Organization and World Trade Organization, Geneva, pp. 49-84.

M. McMillan, D. Rodrik and C. Sepúlveda (eds.) (2017)

Structural Change, Fundamentals, and Growth: A Framework and Case Studies, International Food Policy Research Institute.

G. Michaels, A. Natraj and J. Van Reenen (2014)

“Has ICT polarized skill demand? Evidence from eleven countries over twenty-five years”, The Review of Economics and Statistics, Vol. 96, No. 1, pp. 60-77.

S. Miroudot and C. Cadestin (2017)

“Services in global value chains: from inputs to value-creating activities”, OECD Trade Policy Paper No. 197.

National Board of Trade Sweden (2016)

The servicification of EU manufacturing: Building competitiveness in the internal market, Stockholm. Available at: www.kommerskollegium.se/globalassets/publikationer/rapporter/2016/publ-the-servicification-of-eu-manufacturing_webb.pdf (last accessed on 5 August 2024).

G. Nayyar, M. Hallward-Driemeier and E. Davies (2021)

At your service? The promise of services-led development, World Bank.

H.K. Nordås and D. Rouzet (2017)

“The impact of services trade restrictiveness on trade flows”, The World Economy, Vol. 40, No. 6, pp. 1155-1183.

OECD (1997)

Designing new trade policies in the transition economies, Paris. Available at: https://one.oecd.org/document/OCDE/GD(97)199/En/pdf (last accessed on 31 July 2024).

OECD (2017)

OECD Reviews of Evaluation and Assessment in Education: Romania, Paris. Available at: www.oecd-ilibrary.org/education/romania-2017_9789264274051-en (last accessed on 8 August 2024).

C. O’Reilly and R.H. Murphy (2022)

“An index measuring state capacity, 1789-2018”, Economica, Vol. 89, No. 355, pp. 713-745.

P. Paetzold and O. Riera (2020)

“Global value chains diagnostic – Case Study: Automobiles – Made in Morocco”, EBRD. Available at: www.ebrd.com/documents/admin/gvc-automobiles-in-morocco.pdf (last accessed on 9 August 2024).

T. Porzio, F. Rossi and G. Santangelo (2022)

“The human side of structural transformation”, The American Economic Review, Vol. 112, No. 8, pp. 2774-2814.

A. Rahal (2012)

“Plan de développement de l’industrie marocaine”, Moroccan Ministry of Industry, Commerce and New Technologies. Available at: www.finances.gov.ma/Publication/dtfe/2012/2686_pdim_rabat_20_6_12.pdf (last accessed on 21 August 2024).

D. Rodrik (2013)

“Unconditional convergence in manufacturing”, The Quarterly Journal of Economics, Vol. 128, No. 1, pp. 165-204.

D. Rodrik (2016)

“Premature deindustrialization”, Journal of Economic Growth, Vol. 21, No. 1, pp. 1-33.

D. Rodrik and R. Sandhu (2024)

“Servicing development: Productive upgrading of labor-absorbing services in developing countries”, CEPR Discussion Paper No. DP19249.

J.D. Sachs (1996)

“The transition at mid decade”, The American Economic Review, Vol. 86, No. 2, Papers and Proceedings of the Hundred and Eighth Annual Meeting of the American Economic Association, San Francisco, 5-7 January 1996, pp. 128-133.

N. Saidi and A. Prasad (2023)

“A mercantile Middle East”, Finance & Development Magazine, International Monetary Fund, September. Available at: www.imf.org/en/Publications/fandd/issues/2023/09/a-mercantile-middle-east-nasser-saidi-aathira-prasad (last accessed on 1 August 2024).

J.M.C. Santos Silva and S. Tenreyro (2006)

“The log of gravity”, The Review of Economics and Statistics, Vol. 88, No. 4, pp. 641-658.

UNCTAD (2024)

Global economic fracturing and shifting investment patterns: A diagnostic of 10 FDI trends and their development implications, Geneva. Available at: https://unctad.org/system/files/official-document/diae2024d1_en.pdf (last accessed on 20 August 2024).

UNIDO (2010)

Industrial Statistics – Guidelines and Methodology, Vienna.

S. Wettstein, A. Liberatore, J. Magdeleine and A. Maurer (2019)

“A global trade in services data set by sector and mode of supply (TiSMoS)”. Available at: www.wto.org/english/res_e/statis_e/daily_update_e/tismos_methodology.pdf (last accessed on 4 August 2024).

World Bank (2020)

World Development Report 2020: Trading for Development in the Age of Global Value Chains, Washington, DC.

WTO (2019)

World Trade Report 2019: The future of services trade, Geneva.

Y.H. Zoubir (2020)

“Expanding Sino-Maghreb Relations: Morocco and Tunisia”, Chatham House. Available at: www.chathamhouse.org/sites/default/files/CHHJ7839-SinoMaghreb-Relations-WEB.pdf (last accessed on 22 August 2024).